What Schools Need Right Now: The Power of Carol Miller Lieber’s Guided Discipline

Larry Myatt

Preface

I spend a good deal of time in and around schools, talking and working with educators at all levels. These days, in so many visits and conversations, I am struck by a consistent question, what can we do to manage the troubling student behaviors we’re seeing? Fortunately, I can respond without hesitation. Here’s why….

Behind the worry and stress so many schools are experiencing, there are some powerful forces at work:

The academic/socialization recovery from the Pandemic that people expected is proceeding far more slowly than we’d like.

An emergency declaration of childhood mental health remains in force from the Children’s Hospital and Academy of Pediatrics people. Can you imagine that? An emergency declaration! And yet, so many school boards and superintendents don’t realize it or fail to take heed.

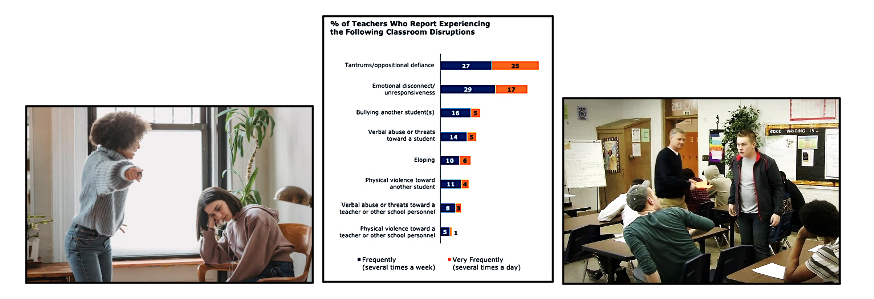

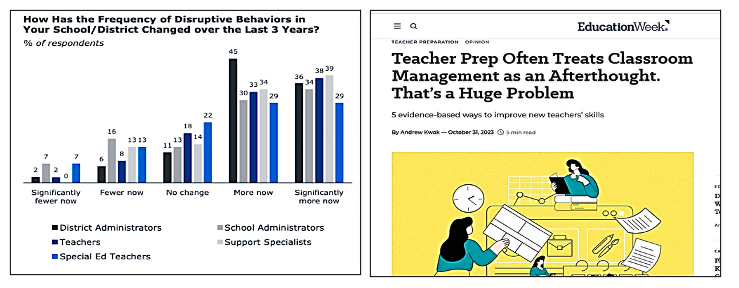

Teachers are saying in every survey that it’s much harder to work with young people and their caregivers.

Early career teachers routinely state that they got little or no helpful university training in managing classroom behaviors, nor did they get it in their school-based practica. Its trial-and-error for too many of them and they’re stressed.

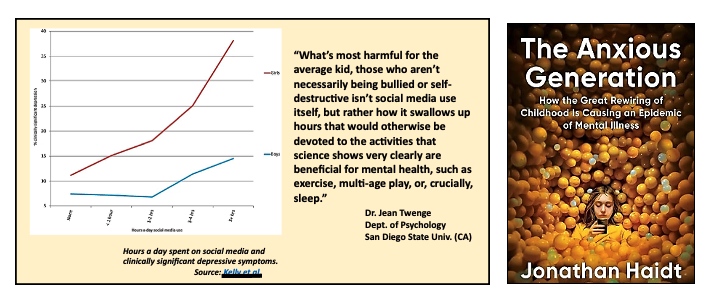

Compounding the challenge is the generational change in how our young people are growing up. It has of late become fully apparent, characterized by the loss of multi-age, neighborhood play, insidious technology algorithms and the onslaught of social media, hurricane-force winds that render the old ways of dealing with unwanted behaviors in school increasingly ineffective. Schools need more resources and support at/from the societal and policy levels, but more immediate help is required.

As one might expect, a proliferation of well-intentioned fixes has emerged, the majority for profit, claiming to address these issues. Some of them offer helpful ingredients, but partial approaches don’t meet the need. I can honestly say at this time there are none on the market that provide what schools really need. Some popular or mandated programs such as PBIS or Restorative Practices may unintentionally compound the challenges.

The good news is that there’s a comprehensive blueprint available that can address many of the student-centered challenges facing schools, an approach that provides the skills, tools, and outlook staff members need but seldom get. If implemented carefully and conscientiously over time (i.e. the 3-5 years it takes any complex initiative to successfully embed in a school), it will provide not only the right ingredients to help students do better in academic and school social settings, but young people can then use the skills and language attained to grow into a productive and rewarding adulthood.

My strongest recommendation? Revisit the work of Carol Miller Lieber and Guided Discipline. Please read on and contact us for support.

Where We’re At In Schools:

Our national policy fixation on testing over the past two decades has resulted in a decrease in training and support for both in-service and beginning teachers in understanding youth development and managing today’s classroom environments. Nor have we been paying enough attention to the generational change in growing up and all that has come with it. Sadly, excellent school culture programming like Guided Discipline and advisories, and stout academic practices such as portfolios, exhibitions and extended projects that were taking root in the late 1990’s have fallen by the wayside.

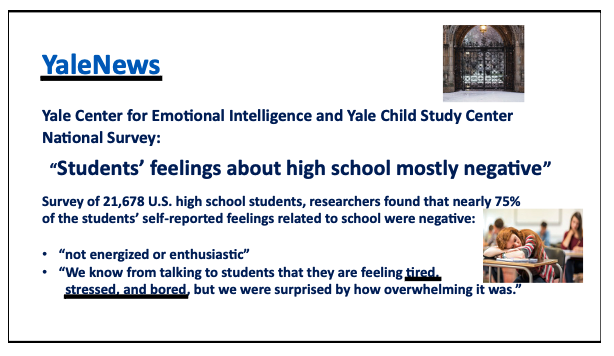

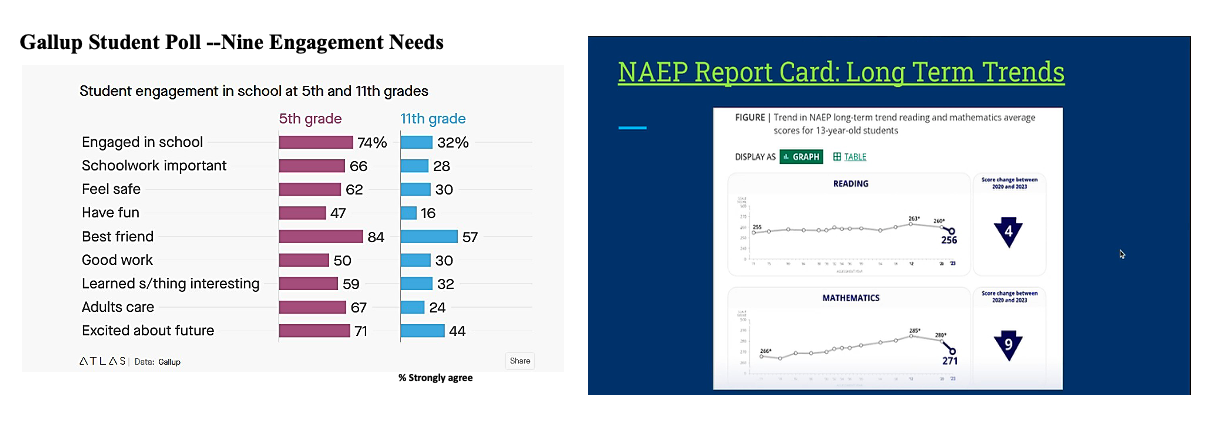

The fragmentation of learning caused by our century-old allotment of time and piecemeal approach to subject matter already dampen student curiosity and suppress achievement measures. Add to that our two decades of teach-to-the test and we can understand why more and more young people have become disinterested in classroom learning and the trappings of school life (see the Yale Center study pictured above). Classroom boredom, the on-going stress of managing the scads of content to memorize, and little quality time on meaningful subject matter they might choose have created conditions for student buy-out. The Pandemic caught us napping, to put it mildly, and we’re paying the price.

How I Learned About Guided Discipline

Let’s get down to the why and how of Guided Discipline.

In the early 2000’s, after two decades as founding principal of Fenway High School in Boston, I became the Headmaster-on-Assignment for the Boston Public Schools Office of High School Renewal. It was a well-funded office, with a small but potent crew of smart and experienced people, with regular consultation with higher ed, work force, and organizational development partners.

Our first significant task was the conversion of three large, comprehensive high schools with sagging achievement and attendance into eleven new high schools of less than 400 students. Each new small school had a “design team” including teachers who signed up for those units specifically, as well as both higher education and community-based partners. New leaders were chosen specifically for a good fit for the school’s mission .

Our HSR Office was responsible for supporting the initial vision-building, the creation of curriculum frameworks, and developing positive team and school cultures.

With that culture-building work as our centerpiece we welcomed the eleven schools to an intense, kick-off professional development week. Needless to say, a critical element would be the choice of a proven program to establish a positive school culture, with tight guiding principles and the requisite tools and resources . Luckily, as a district member of several school restructuring networks, we had contacts and resources in and from a number of cities. We did our homework, and with the help of ESR, a hub for teaching social responsibility and later to be known as Engaging Schools, our clear choice was Guided Discipline.

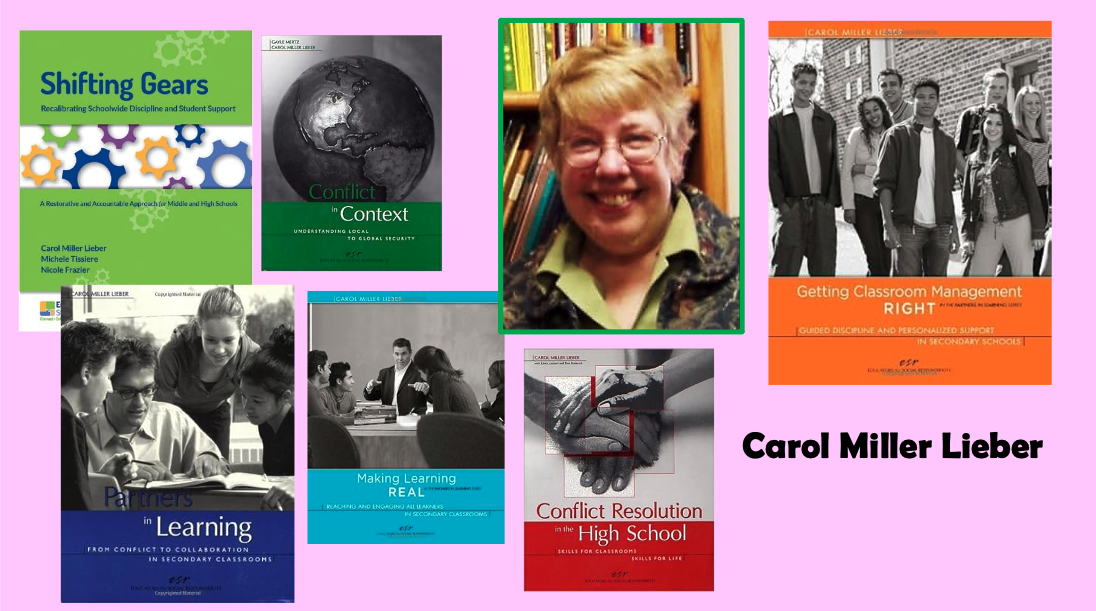

Carol Miller Lieber

The “main brain” behind Guided Discipline was Carol Miller Lieber, a gifted yet down-to-earth thinker and educator. She taught in both middle and high school, was a clinical professor of teacher education, an author, and a designer of programs and professional development on the national level. She also founded and led the Crossroads School in St. Louis, which spawned a generation of thoughtful progressive educators.

At the time of publication, Getting Classroom Management RIGHT, with Guided Discipline, was a welcome alternative to the decade-old “zero-tolerance” approach which not only punished and exiled thousands of students with a “behave-or-else” stance. Zero-tolerance policies also short-circuited the growth and development of a generation of teachers who were “relieved” of chronic disruption by policies of long-term suspension, expulsion, and banishment to holding tank “alternative schools.” Adults could handily avoid working with non-compliant students by getting rid of them.

One of the first educators to recognize the significance and potential of Guided Discipline was Dr. Pedro Noguera, now Dean of the Rossier School at USC, and then the Director of the Metropolitan Center for Uban Education at NYU. He observed for ESR, “creating an orderly environment is essential for optimal teaching and learning, and Guided Discipline does that by moving beyond punitive approaches and placing greater emphasis on relationship-building and a student’s intellectual engagement.”

One of the first places Miller Lieber found success was her work in the Chicago Public Schools. Known for their struggles to manage student disruptions, CPS had become known for their “zero-tolerance” stand and soaring expulsions and suspensions. Thoughtful educators and community members were border-line desperate for something different to bring into their schools. Miller Lieber and her ESR colleagues offered a refreshing new approach. One that worked.

Her experiences and vision for creating safe, positive, and high-functioning school enjoyments were vast and we at HSR were fortunate to have our new Boston schools spend that full week with her prior to launch. As a principal, I was drawn in by the way she thought through the complexities of school culture and youth development and how they could mesh.

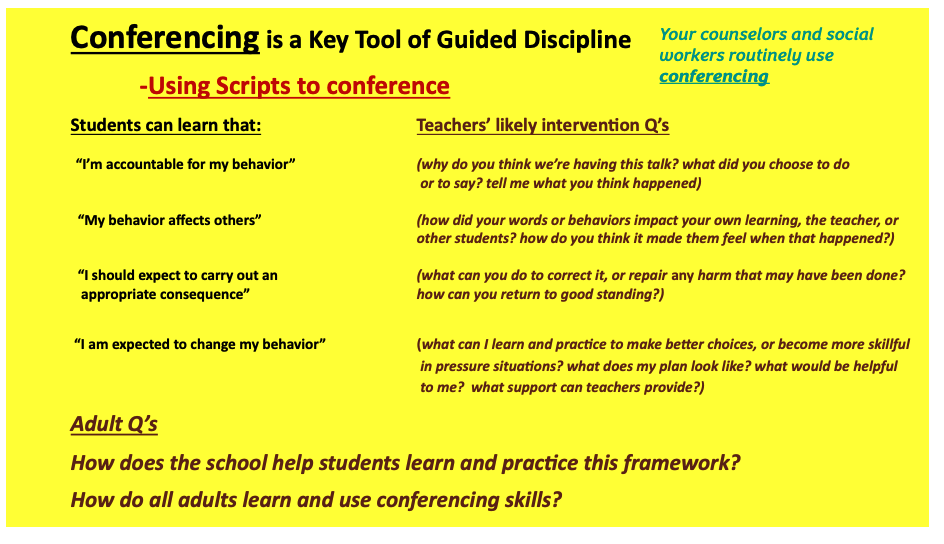

We saw right away as she worked with teachers, how her tools, language, and frameworks made sense and could quickly take root. During the week teachers of all levels of experience took to the conferencing skills she modeled and the ways in which she would reframe behavioral challenges into opportunities to engage. Something new and different they enjoyed were opportunities to reflect on how they presented themselves in their classrooms, routines and structures for student problem-solving and success, and drama-free invitations for them to self-correct. That notion, to “leave out the drama,” and providing ways for students to save face or repair relationships helped distinguish Guided Discipline as good for adults as well as young people. The buy-in and appreciation were immediate.

The Core Ideas

As stated by Miller-Lieber, the design and intent of Guided Discipline is appropriately deep and broad:

to help students take responsibility for their behavior or academic problems,

to understand the effects of their behavior on themselves and others, and

to learn and practice behaviors that are more skillful, responsible, and productive.

In other words, its fully about learning and practicing the rules of a successful journey through life.

I’ve worked in more than one hundred schools, much of that time focused on helping schools in low-income areas, urban and rural, develop approaches to managing student behavior and increasing wellness support. What I would add to Dr. Noguera’s observation is the way Guided Discipline, unlike many other approaches, does not overlook using the power and skill of adults as problem-solvers and role models, or expect young people to manage change on their own or through negative consequences.

Although originally intended for a mostly middle and high school focus, I should mention the many successes of elementary schools I’ve witnessed using Guided Discipline language and tools long before students leave for the upper grades. Guided Discipline concepts are precisely what are needed foundationally, thereby contributing to making other approaches such as Restorative Practices, PBIS, “Full Value”, Conscious Discipline, etc., more likely to succeed as additive ingredients, if desired.

Why does it work so well?

Guided Discipline is a careful combination of guided instruction and support, interventions and meaningful consequences that helps students learn and regularly practice more skillful behaviors and responsible decision-making. In contrast to punishment or permissiveness, meaningful consequences are a part of the puzzle to be solved directly with the student.

Much of the power of Guided Discipline flows from its central assertion that all good discipline is self-discipline. Even to adults, that notion can seem vague and not so important until we think about self-discipline in our own lives: not driving 60 in the 30-mph Zone, getting to our taxes on time, showing up punctually to pick up the kiddos at school or a friend’s, renewing licenses and permits, paying our bills, even staying off the late-night pizza. Somehow, most of us learn that way of life and that it helps us to stay out of trouble and to live in gratifying and productive ways.

Something other approaches often assume is that all young people bring a social/emotional vocabulary to school and can employ personal assertiveness rather than aggression or passivity . We may also assume they’ve developed “mental models” for use in situations where empathy, apology, or conflict arise . These are certainly things we’d like every child to experience as they grow up, but it doesn’t work that way. Instead, Guided Discipline teaches the language and the mental models required through conferencing, scenarios, and practice with adults and peers. Rather than the limited range of reactions we often see and hear students bringing to complicated experiences (“good-bad-sad-mad-glad”), we can move students into a new comfort zone with more helpful and appropriate ways of matching their speaking to their feelings. That modeling and “gradual release” from adult to student becomes the central work.

As mentioned above, unlike some approaches, in Guided Discipline there remains a clear and important role for a wide range of graduated and differentiated consequences and interventions. The idea is to match appropriate consequences to the frequency and severity of a problem behavior and provide the kind of instruction and support that best matches the needs of individual students. Unlike punishment-and-control approaches, or overly focusing on inauthentic rewards , Guided Discipline is “present and future oriented.” The idea of “doing better next time” is a key concept, and focuses on the student’s need to regain control, self-correct, redirect focus, and get back on track. Positive and negative consequences are viewed as natural outcomes of the choices students make.

Thinking about the importance of school in youth development, it makes complete sense for teachers to play a central role in helping students be ready to learn. Rather than butting heads as adversaries, or having students left largely alone to negotiate complicated problems, a teachers’ guidance, coaching, and support helps students develop greater personal self-discipline and foster classroom habits and routines that create a more welcoming and gratifying learning environment.

Learning the Rules of Life

One of the hallmarks of “Helping Students Be Accountable” is the central role of these four axioms:

“I’m accountable for my behavior”

“My behavior affects others”

“I should expect to carry out an appropriate consequence”

“I am expected to change my behavior”

Educators who have successfully practiced Guided Discipline routinely speak about the conferencing involved as helping young people learn the “rules of life” and how they make so much sense at every age. Each of the four comes with some questions to ask oneself : how did I get here? how did what happened make others feel? how do I get back in good standing? what could I do differently and better next time? As students imagine answers to these questions, with help from others and increasingly on their own, they can create new mental models of success as they also learn the accompanying language.

I could go on about the power and promise of Guided Discipline but I’ve laid out the basics. And we’re proud to say that we have become a high-impact provider of Guided Discipline support for schools. If you’re part of a school community trying to figure out ways to help reduce disruption, support staff, and help young people do better and appreciate the chance, I cannot recommend any programming more fully.

I’ll close by offering a huge, but sadly, posthumous thank-you to Carol, in memory of her many years of work on behalf of young people, families and educators. We lost her in 2022.

I’m happy to take calls or emails to discuss it on a deeper level and keep in mind that we provide high-impact professional development in implementing it across a school or district.

Larry Myatt, Co-Founder, ERC

larrymyatt1@gmail.com

Note: The best collection of Carol’s Guided Discipline tools and approaches is found in Getting Classroom Discipline RIGHT, published initially by ESR. Copies are still available online from several publishers and warehouses and we extensively use and have updated many of those items.